By Tara Spencer

In the late 1930s, a group of men in New York City decided they wanted to show off their culinary talents to their peers. Thus, the Society of Amateur Chefs was formed.

Their first organizational meeting was held at the Hotel New Yorker in October, 1938, and was comprised of “men whose hobby is preparing and serving their own favorite victuals.” It was decided they would meet on Thursdays, as that was the traditional “housemaids’ night off.” These dinner meetings presented an opportunity for members to demonstrate their skill in the “male interpretation of good cooking,” according to a New York Times article from Oct. 14, 1938.

Founder (and later executive director and president) Ben Irvin Butler declared November 3, 1938 as the day marking the “emancipation” of men who enjoy cooking. (This was the date the society was officially formed.) This declaration was made in an article Butler wrote that appeared in the Morning World-Herald on August 12, 1940.

The organization disbanded for some time during World War II, but reconvened in the late 1940s, with chapters popping up across the country.

Their reformation and ensuing popularity were, in part, a reaction to what one man (ironically, the feature and woman’s editor of the St. Louis Dispatch) described as “a de-caloried and vitamized society where every woman aspires to be a broomstick.” Apparently, some men at the time felt they were being made to eat smaller, healthier meals by their wives, forcing them to cook their own food when they got a hankering for something hearty.

Primarily thought of as a meat-and-potatoes (and corn) state, Nebraska was an ideal place for a chapter to form. That’s not to say members strictly stuck to steak, though. These men incorporated many different ingredients while occasionally drawing on other regional cuisines to make their meals of substance. With their desire for more indulgent meals, there was a seemingly strong preference for rich, French-influenced creations.

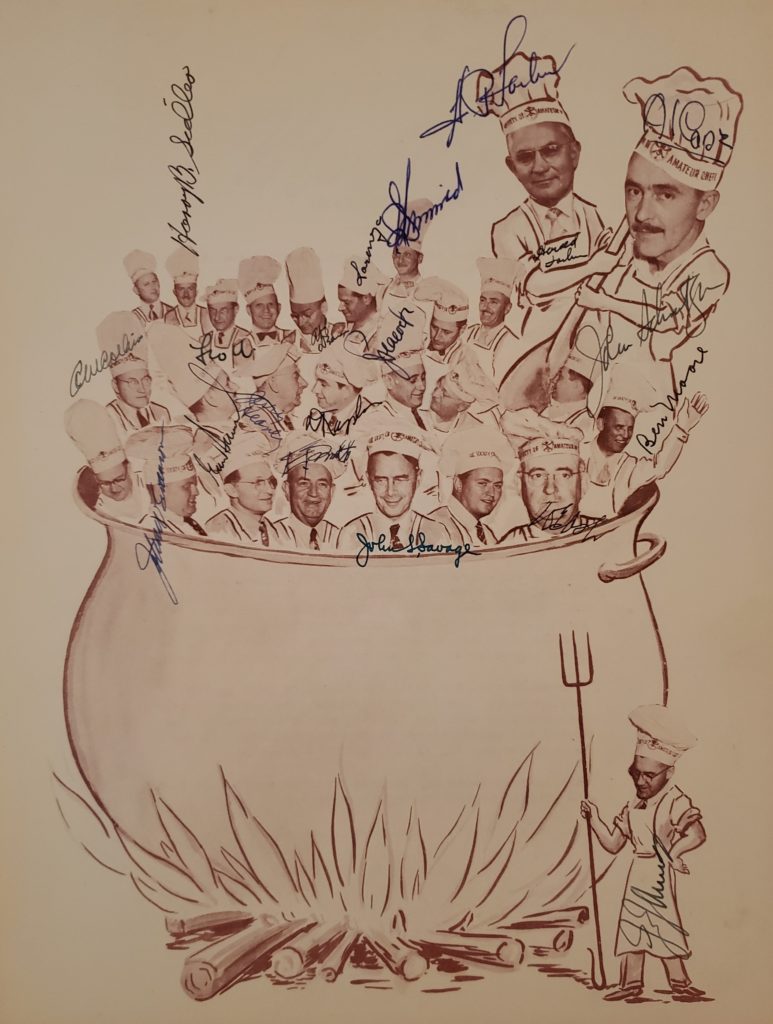

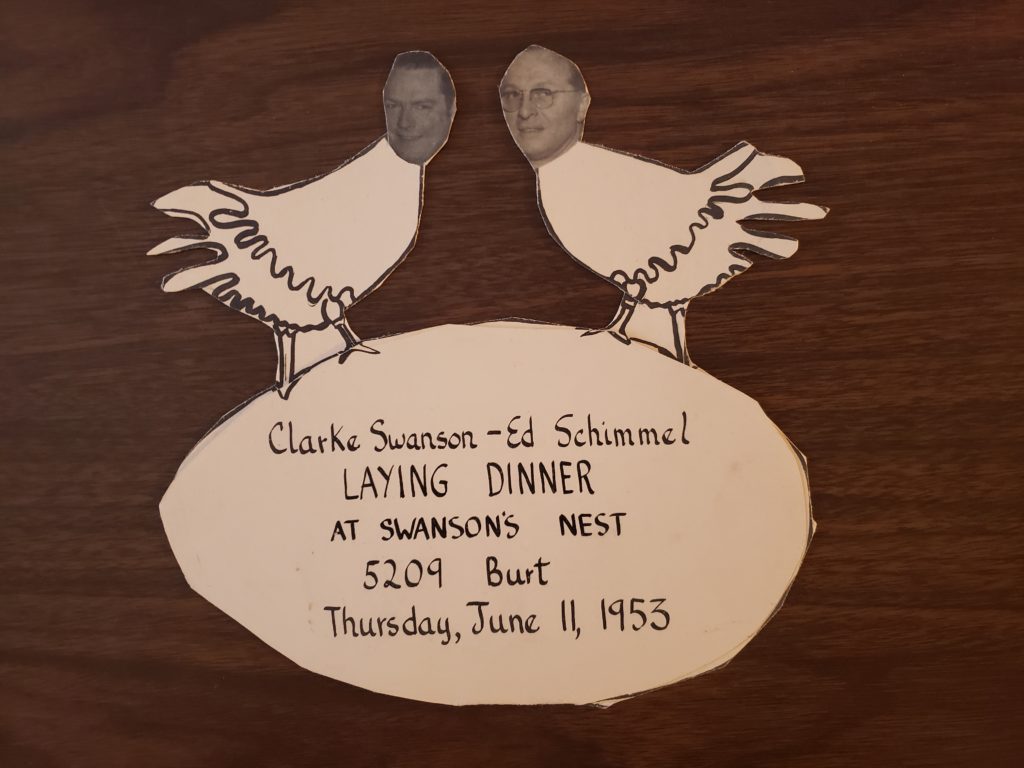

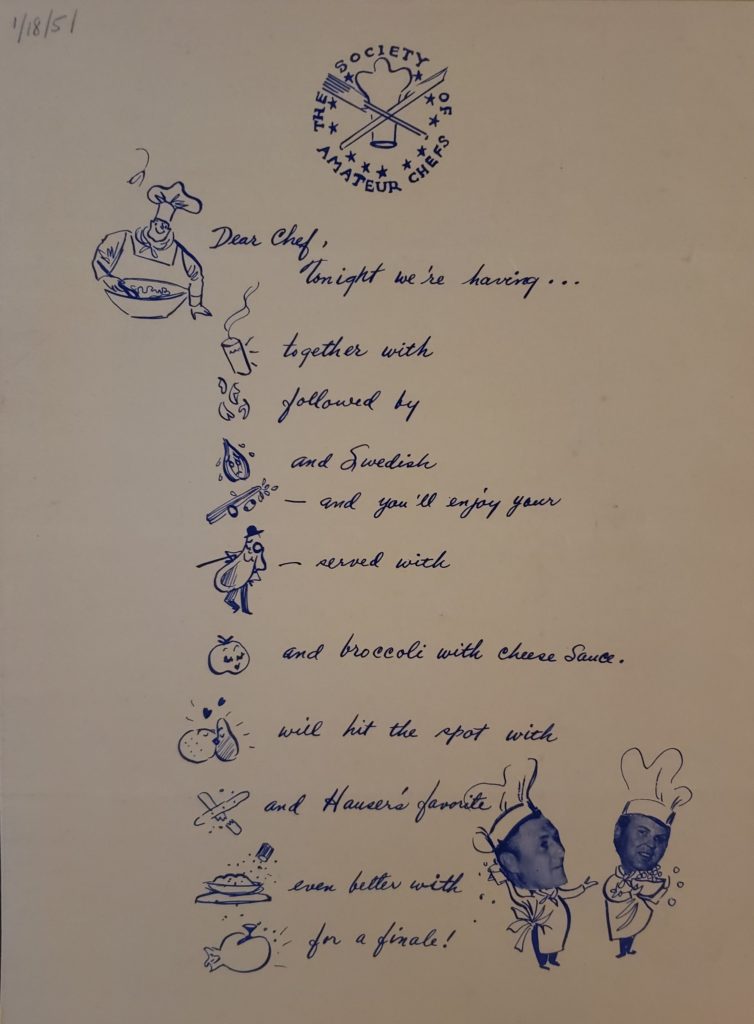

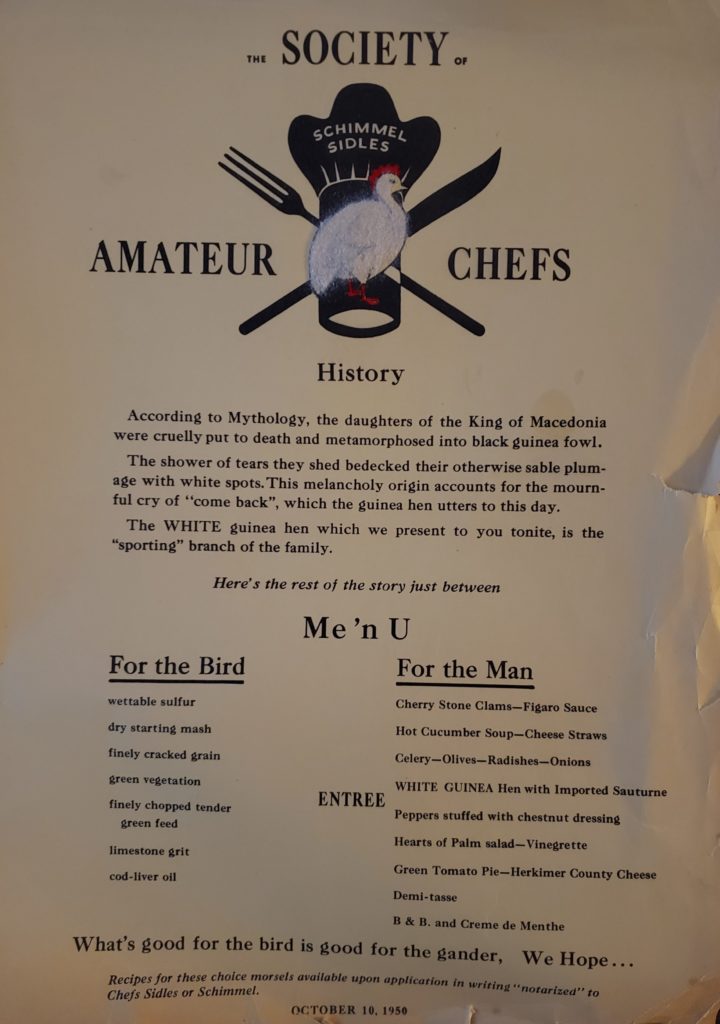

The Douglas County Historical Society recently acquired a collection that includes memorabilia from the Omaha chapter of the Society of Amateur Chefs, including membership lists, meeting reports, newspaper articles and ads, invitations, and many menus. The society’s invitation-only dinners presented their invitations and menus in a humorous, whimsical fashion using clever designs and tongue-in-cheek wording. Oftentimes, they would incorporate representations of the evening’s hosts/cooks into the design.

Omaha’s chapter included some names that pepper the city’s history, such as Schimmel, Swanson, and Storz. Unsurprisingly, these names are also associated with the food and drink industry.

Listed in the membership registry, Edward Schimmel was the manager of the Blackstone Hotel (which could explain why many of their dinners seemed to take place there). Also found in several of the registries was Arthur Storz of Storz Brewery family fame. Clarke Swanson, of what would become the TV dinner empire, makes an appearance in the pieces of ephemera, notably on an egg-shaped invitation, on which his head is placed atop the body of a hen, alongside similarly attired cohost Ed Schimmel.

The New York chapter had a slightly more eclectic mix of characters, with one New York Times article mentioning attendees Jack Dempsey, Christopher Morley, and Lowell Thomas, as well as cartoonists Ham Fisher and Charles Biro.

Some of the society’s members were featured in ads for Libby’s corned beef hash, in which they would provide unique recipes that incorporated the hash. One such advertisement featured a “Hash Hawaiian” by author, explorer, and member of the society “Bob” Ripley.

The Omaha chapter’s big coming-out was featured in the April 11, 1948, issue of the Sunday World-Herald Magazine. The men met in the Fern Room of the Blackstone Hotel, natch. The new club had a seven-course dinner lasting three and a half hours, followed by a brief business meeting in which they voted to apply to join the national society—a formality, as they had already been invited by the national group.

Twenty-one men attended at this first meeting, and it was later decided that the maximum number of members should be limited to twenty-eight. They planned to have ten dinner meetings a year, at a cost of $7.50 per person, with two people hosting. It was strictly stated in their rules that members must be willing to “promote the culinary interest of the group.” It was clear that they took their “amateur cookery” seriously, further stating that many members were not interested in a “stag dinner group,” meaning they did not want members to simply hire a professional to plan and make the meal.

This fell in line with what the originators of the society stipulated—that members must cook for a hobby. Though it should be noted that they did not stipulate they be good at it. Rather, it seems they considered it a given.

Reading through articles related to the Society of Amateur Chefs, one notion that stands out is the belief that men are simply better at cooking. The New York chapter went so far as to pass a resolution to that effect.

Given the fact that women had been confined to the kitchen for much of Western history, this was a tough bite for some to swallow. Some women, and men, did push back. A former Mrs. Omaha, M.E. Arnold, determined that men do well when focusing on one dish or style of cooking. “If women could concentrate on special dishes for special occasions, we’d do a better job than the amateur cook,” she was quoted as saying in a World-Herald article. Dan Powers, noted as being the secretary of the Association of Amateur Chefs in Omaha, was quoted in the same article as saying amateurs are good at cooking because they like food. “Men have the edge there,” he said, as though women of that time simply did not like food.

A positive aspect of the organization is that they did seem to believe that more men should be interested in cooking, especially among younger generations. One article noted that younger men tended to view cooking as unmanly, or “sissy.”

While this sentiment surely still exists in some, cooking has become a more acceptable hobby for men over the last few decades. Cooking as a form of employment? Well, the culinary field has been strongly dominated by men for decades, with women typically making up around a quarter of chefs working in the industry in the U.S.

The men of the Society of Amateur Chefs once said they might “give their wives a treat” by inviting them to a session once a year. But women don’t have to wait to be invited. They can make their own meals—and their place is only in the kitchen if they want it to be.

Sources:

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1951/07/14/86468431.html?pageNumber=16

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1938/10/14/issue.html (Pg. 25)

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1952/01/20/93557250.html?pageNumber=202

https://www.encyclopedia.com/food/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/women-and-food