By: Elise O’Neil

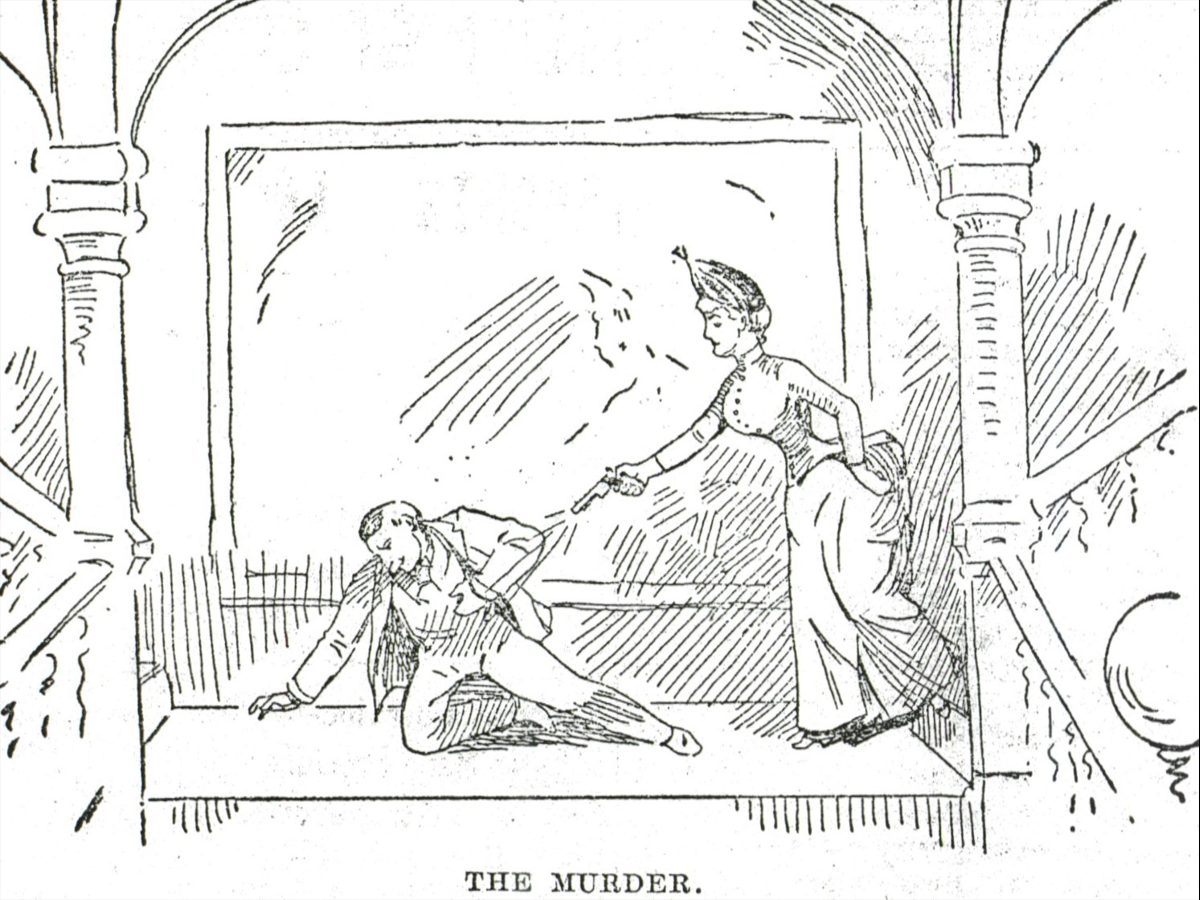

On November 17, 1888, Elizabeth Beechler shot her husband to death in the lobby of the Paxton Hotel. There was no doubt that she was the culprit. Multiple witnesses watched her follow him to the staircase, firing a revolver in his general direction. She was even heard to exclaim, “I have shot my husband!” before handing off her gun to another hotel guest and collapsing into a faint. Without question, she was the cause of this man’s demise. Nobody disputed this.

The Paxton Hotel, c. 1886

Illustration of Libbie Beechler in the Omaha World-Herald.

Why, then, was she tried and acquitted of the crime less than 5 months after perpetrating it? Maybe 200 years earlier, before literacy rates skyrocketed in the United States and newspapers were printed cheap and fast, the answer to this question would have been lost to the mists of time. But the reporters staffing the World-Herald in 1888 were as intrepid as they were unethical, and the Douglas County Historical Society has filed away pages and pages of their prodigious output concerning this case.

The reporting on the trial was exhaustive and scathing, incorporating even the most insignificant of details while viciously roasting various side characters. But long before the trial commenced, in just the first 48 hours after the murder, reporters from local publications were digging as deep as they could to take advantage of the growing sensation. They joined the looky-loos at the Paxton, attempting to catch glimpses of the hotel servants cleaning blood out of the Turkish carpets. They went to the morgue where some of them succeeded in viewing the corpse. They listened in at the inquest, soaking up every little nugget about the bullet’s trajectory throughout the man’s body. One indefatigable Herald man even managed to elude officials and temporarily achieve an “unobstructed view” of the accused in her jail cell.

Not only did these reporters provide posterity with copious amounts of information about the crime and its aftermath—they were likely one of the main instigating factors in Elizabeth Beechler’s eventual acquittal. Amidst sensational descriptions of the victim flailing his arms before toppling down the staircase and “the life blood spurting from his mouth,” two facts remained consistent throughout every reporter’s tale. First, Elizabeth Beechler had killed her husband. And second, said husband had recently deserted her and married another woman.

The latter of these facts immediately garnered her sympathy with the public—particularly with women. For a Late Victorian woman with no family money, desertion by one’s spouse could result in the direst of straits. Respectable ladies across Omaha surely put themselves in this unfortunate woman’s shoes and felt for her in her distress. Two women were even accosted by a World-Herald reporter as they left the jail, having just delivered an “elaborate meal” including “some very fine fruit and a pitcher of cream” to the accused.

Of course, the father of the dead man had no sympathy for his son’s erstwhile wife, claiming to reporters that she was of “bad character” and implying that the two had never even been married at all. However, his voice seemed to be alone in the sea of others who took up for the woman, appearing to be altogether unimpressed with the dead man’s womanizing career. One of the father’s closest business associates told reporters that he was unsurprised at this turn of events, as the murder victim was a “prodigal son” who “threw…aside” his many advantages in life and “seemed wholly unable to resist temptation.”

Riding and encouraging this wave of sympathy for the woman they dubbed “the murderess,” the papers rarely failed to describe her in a flattering light, presenting her as “pale” with “unusually large blue eyes and dark hair.” In the earliest stages of reporting, she was presented as entirely respectable, having previously lived in a stylish area of Chicago. One notice even opined that she ought not to be put on display and that she was far too innocent a character to be sharing a cell with the “procuress” who was her current cellmate. Just two days after the murder, the World-Herald declared that “public sentiment and sympathy (were) much in favor of the woman.” All of these very public opinions and descriptions placed the accused at a significant advantage by the time her trial rolled around.

Illustration of Harry W. King, Jr. in the Omaha World-Herald.

But let’s back up for a moment. Who was Elizabeth Beechler? And who had her husband been before succumbing to his injuries? Elizabeth Beechler was referred to in the papers by various derivatives of her Christian name, including Eliza, Lizzie, and Libbie. She seems, however, to have consistently referred to herself as Libbie, so we’ll go with that. Originally from Cleveland, she came from what all the reporters agreed was a “poor” family and lived in obscurity in Ohio until she met her husband. He swept her off her feet and away from the country hotel in which she was working, taking her to live with him in Illinois.

Image of the lobby of the Paxton Hotel.

Her husband, in contrast, was more of a known quantity by the time of his murder. The son of Chicago business mogul Harry W. King, Sr., Harry W. King, Jr. was a 30-year-old college graduate who had already been divorced once when he met Libbie Beechler. Soon after the two crossed paths, in October of 1886, the young King took his newest conquest to Quincy, Illinois, where he had a friend who may or may not have been a minister marry the two in secret. Libbie was assured that the marriage was legally binding, and the couple proceeded to set up house in Quincy and later in Chicago, living as husband and wife. One red flag in this arrangement which Libbie chose to ignore was that her husband insisted they live under false names so that his father wouldn’t get wind of the marriage. But she was a decade younger than her world-wise husband, and he was not only paying for her sister to attend school at a convent in Chicago, but also allowing her 4-year-old brother to live with them as a surrogate son. Despite the subterfuge, this was a huge step up in life for a poor girl from Cleveland.

Yet the red flags continued to wave. Later, Libbie would claim that Harry had beat her in the streets of Quincy, resulting in the miscarriage of their unborn child. Further, twice Harry deserted her, leaving her destitute. Both times his father dispatched lawyers who held out the promise of lump sum payments if she would sign papers relinquishing her claim to him. The couple reunited and continued their life together soon after the first desertion, but upon the second, Harry absconded to Missouri where he married an 18-year-old named Alice Duffy. It was reading of this marriage in the paper that spurred Libbie to board the train to Omaha where the newlyweds were reported to be living at the time.

And that brings us to the crime. According to witnesses at both the inquest and the trial, Libbie checked in at the Paxton early in the morning as soon as she arrived in Omaha. She then asked to be shown to the young Mr. King’s room, where she knocked on the door and announced herself. Harry did not invite her in, and instead the two made their way to the parlor above the lobby where they engaged in a chat for some 15 to 20 minutes until the shots from her revolver began to ring out. Witnesses saw Libbie pursuing her husband while continuing to shoot as he ran from her, tumbled down the balcony stairs, and collapsed in a bloody heap on the landing. Libbie was not, it turns out, a very good shot, as only one of the four bullets struck him. Nevertheless, he expired within minutes, being unable to speak and therefore making no dying declaration.

World-Herald illustration of Libbie Beechler shooting at Harry W. King, Jr. in the lobby of the Paxton Hotel.

The trial itself was appointment viewing for Omahans who had the time. Professionals with flexible schedules and middle-class women who kept house were the main spectators. Arriving hours before proceedings began each day, these casual viewers packed the courtroom and jostled for seats—some bringing luncheons so that they didn’t have to give up their positions during the midday recess. Those times when the trial wasn’t proving to be dramatic enough copy, the trusty reporters from the World-Herald and the Bee could be counted on to take shots at the spectators to add a little color to their stories. One notice referred to the viewing public as “the vulgar herd” while numerous other reports devoted paragraphs making snarky comments about the women in the audience, noting that they far outnumbered the men.

But who could blame these thrill-seekers for their determination to land good seats at the best show in town? Though there were moments of tedium to allow for the serious administration of the law, there were enough outbursts and scandalous revelations to keep even the most jaded housewife engaged. The opposing lawyers were constantly objecting to one another’s statements, detailed descriptions of gore abounded, and the defendant herself was incredibly exciting to watch. Dressed in “widow’s weeds” in deference to the husband she had recently killed, she was an array of emotions—at turns chatting amiably with her representation and at others audibly wailing in frustration. Several times she had to be taken into a back room to be calmed down due to excessive dramatic swooning.

Illustration of Libbie Beechler swooning in the Omaha World-Herald.

The jury selection for this trial was also more intensive than most, as the court needed to find 12 men willing to sentence a woman to death. When the pool ran out before reaching the required number, the presiding Judge Groff had to issue a venire compelling more jurors to come to court. Accordingly, the sheriff’s deputies began pulling random men off the streets for that purpose.

The prosecution had a strong case. After all, it was not in dispute whether Libbie Beechler had shot and killed Harry W. King, Jr. The prosecuting attorney merely had to prove that she had meant to do so. The lead prosecutor was a Mr. Mahoney, who introduced numerous witnesses to describe the events leading up to the crime, the crime itself, and Libbie Beechler’s affect and motivation throughout the entire ordeal. Mahoney asserted that the defendant had gotten on the train to Omaha with the sole intention of finding the victim and murdering him. The lynchpin that held this argument together was a letter that Libbie’s team had valiantly fought but failed to have thrown out of the pile of admissible evidence. In it, many months before the crime, Libbie wrote to her husband upon his first desertion that, “If you ever go back on me again, God help you, for I will not let you live.” Tough stuff.

However, the defense seemed to take this damning letter in stride. In fact, the lead defense attorney, a General Cowin, chose to rest without presenting a single witness, insisting that the prosecution had made his case for him. That isn’t to say that he didn’t make his own persuasive argument. During closing statements, Cowin spoke for hours upon his client’s innocence until he was entirely hoarse, floating several novel theories to introduce that little bit of reasonable doubt. He positioned Libbie as the victim in the situation, arguing that she had been betrayed by her husband and bamboozled by the lawyers his father had sent to pay her off. He asserted that the evidence showed she had acted in self-defense, as she had stated that she shot Harry only after he had taken her by the throat and threatened her life. According to Cowin, Libbie was nothing but a loving and dutiful wife, while her husband was a spoiled scoundrel. He took particular relish in the dead man’s last name, “King,” honing in on the American distaste for monarchy and implying that Harry was the disastrous result of the endless indulgence afforded to “royalty.”

Illustration of General Cowin in the Omaha World-Herald.

Early on in his speech he seemed almost to be making a proto-feminist argument, questioning openly how a jury made up entirely of men could possibly be expected to comprehend the inner workings of a woman’s heart—the actions of a woman in love. And then he went an entirely different route in order to claim that Libbie had been temporarily insane when she shot her husband and could therefore not be held accountable for her actions. He argued this point by brandishing a medical textbook and explaining that all women go temporarily insane once a month when menstruation occurs. Perhaps this scientific assessment was the theory that clinched the defense’s victory.

Libbie had maintained the sympathy of the court and the public throughout the trial. Reporters commented that her appearance was favorable despite her months spent languishing in jail. The bailiffs and deputies seem to have taken a liking to her and began chaperoning her on carriage rides around town to calm her nerves after court. (One day, a bailiff even took her on a peaceful ride around Fort Omaha which she seemed to have enjoyed immensely.) And when the jury rendered her “not guilty,” the entire room cheered, utterly irritating an already exasperated Judge Groff. She couldn’t leave the courtroom for a long while thereafter, as a receiving line had formed, and she was obliged to kiss and thank every spectator who had taken in her ordeal day after day.

So why was Libbie Beechler allowed to walk free after killing her husband? Did the jury buy that she was defending her own life? Did they conclude that she had been temporarily addled by her menses and the injustice of all her husband had put her through? They weren’t telling. Perhaps they didn’t even know. One juror was quoted in the World-Herald stating that the 12 men had not even had a discussion over the matter. They had simply walked into the jury room, voted “not guilty,” and unanimously acquitted her of the crime within minutes.

Libbie Beechler had many attributes that endeared her to reporters, the jury, and the general public. She was attractive and personable. She presented herself as a respectable white bourgeois lady. And she was also not local, meaning that no one in Omaha harbored any previously-held assumptions about her or her background. She was a clean slate upon which the public could superimpose their own sympathetic interpretations of a wronged woman. While there were many tales of her husband’s notorious misdeeds flowing into local papers from Chicago, Libbie appeared to have no dark past upon which to capitalize. She was essentially the proverbial “everywoman,” which worked significantly to her advantage.

And she didn’t stick around to change this perception. The day after the trial ended she hopped on an eastbound train with her destination unknown to at least the clambering reporters. She was not heard from in Omaha again.

Illustration of Libbie Beechler clutching her handkerchief in the Omaha World-Herald.

Sources

“What Judge Brewer Saw.” Omaha World-Herald. 18 November 1888.

“Young King’s Career.” Omaha World-Herald. 18 November 1888.

“Mrs. Beechler’s Babe.” Omaha World-Herald. 18 November 1888.

“Mr. Browning Interviewed.” Omaha World-Herald. 18 November 1888.

“Around the Morgue.” Omaha World-Herald. 18 November 1888.

“The News in Chicago.” Omaha World-Herald. 18 November 1888.

“The Inquest.” Omaha World-Herald. 18 November 1888.

“Shot to Kill.” Omaha World-Herald. 18 November 1888.

“The Slayer’s Story.” Omaha World-Herald. 18 November 1888.

“King Senior’s Statement.” Omaha World-Herald. 18 November 1888.

“After the Tragedy.” Omaha World-Herald. 18 November 1888.

“Will Be Commenced Today.” Omaha World-Herald. 2 April 1889.

“She Wore a Widow’s Weeds.” Omaha World-Herald. 3 April 1889.

“She Made a Scene in Court.” Omaha World-Herald. 4 April 1889.

“Morbidly Curious Masses.” Omaha World-Herald. 5 April 1889.

“A Settlement That Failed.” Omaha World-Herald. 6 April 1889.

“Surprised by the Defense.” Omaha World-Herald. 7 April 1889.

“Talking for a Woman’s Life.” Omaha World-Herald. 9 April 1889.

“Her Freedom is Restored.” Omaha World-Herald. 11 April 1889.

“Where Will She Go?” Omaha World-Herald. 12 April 1889.