Medical Arts Building: Omaha’s Original Medical Campus

Natalie Kammerer

Omaha has a strong reputation in the Midwest for its medical resources, and today boasts several state-of-the art complexes that serve as healthcare hubs providing many services on one campus, or even under one roof. This certainly wasn’t always the case, but the history of combined medical facilities in Omaha goes back farther than you might have realized.

Around the turn of the century, Omaha was home to innumerable small hospitals, clinics, sanatoriums, and other medical facilities of religious, secular, private, and public persuasions. Some were large organizations like the Douglas County Poor Farm (originally located on St. Mary’s Avenue, ultimately residing at the location of the current County Hospital near 42nd and Woolworth) or St. Joseph’s Hospital (10th and Castellar), but many others were small private institutions housed in homes or office blocks, for instance, the Birch Knoll Sanitarium at 22nd and St. Mary’s Ave.

In fact, records from the 1920s point to the existence of 16 to 22 different hospitals,[1] an impressive number for a town whose population hadn’t yet topped 200,000.[2] Certainly, there were benefits to having so many small and large facilities distributed across Omaha’s neighborhoods (but still largely centralized in the Midtown and Downtown areas), but many local physicians and other healthcare professionals had a desire to form an association (the Medical Arts Association), and by 1919, property had been purchased at 17th and Dodge Street, and well-known local architects—Thomas Kimball and John and Alan McDonald—had been hired to furnish designs for a 17-story mixed-use structure.

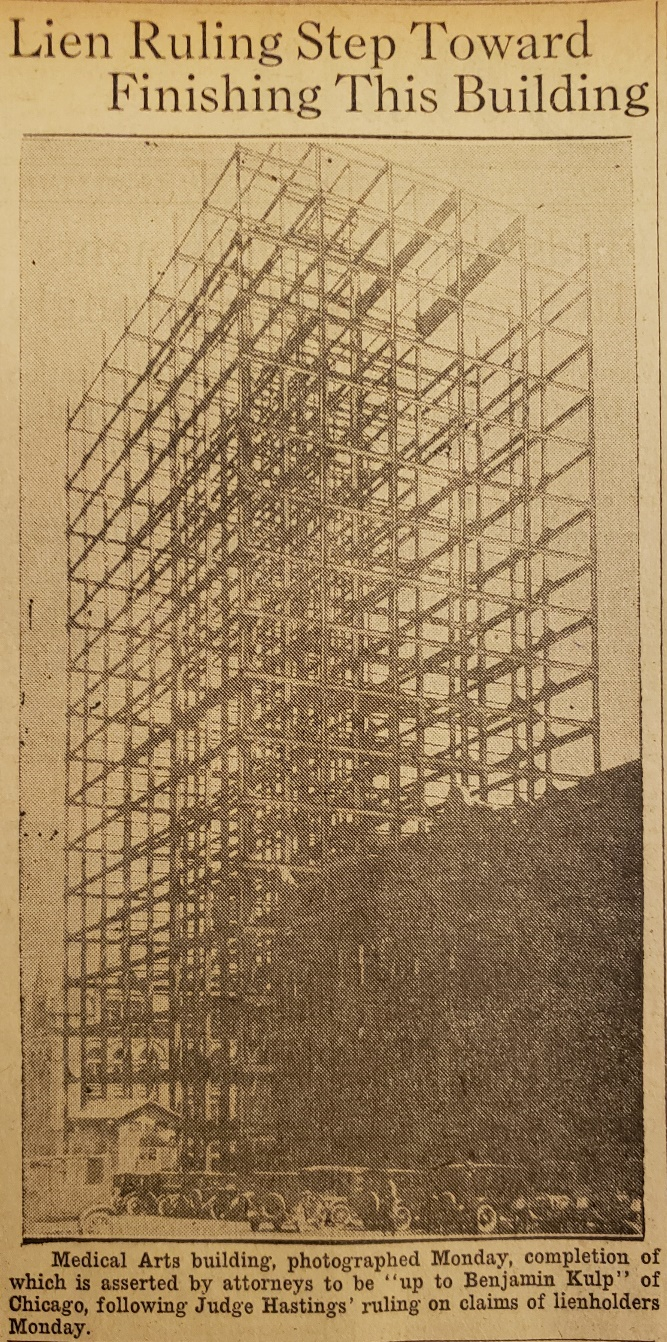

Despite local enthusiasm, construction was delayed due to a rise in the cost of building materials and labor. By September of 1921, construction had begun, and was anticipated to cost about $1.8 million[3]—the largest building project in Omaha at the time.[4] Not long after, though, just as the building’s steel frame was completed, progress came to a grinding halt. Financial issues had arisen again, this time in the form of a legal battle over design and construction fees and a lien being placed on the partially-completed structure. The steel skeleton stood in place for three years before it was bought by the Selden-Breck Company at a sheriff’s auction in 1925. The original architects had pulled out of the project, and it was finished by Crosby and McArthur, with some changes to the original plans.[5]

The steel structure as it stood for three years. Image source: Omaha World-Herald. April 27, 1925.

Work resumes on the building in the fall. Image source: Omaha World-Herald. September 27, 1925.

The building was finally completed in 1926, with a variety of amenities, including: the first electric passenger elevators in Omaha (Otis Signal Control); a 500-seat auditorium for clinics and other professional gatherings; individual lavatories with hot and cold water, electricity, compressed air and gas lines, and the possibility to connect x-ray apparatus in each office; and “in addition to complete men’s toilet rooms on all floors throughout the building, the unusual convenience of a well-equipped combination women’s toilet and rest room…on each floor.”[6]

In 1927, one year after the building had opened, 75% of rentable space had been let, 185 medical professionals had set up shop, and an average of 6,651 individuals took advantage of services in the building each day.[7] Tenants included physicians, dentists, and also such businesses as Barber Dental Supply Co., Robert D. Jones Dental Lab, Medical Protective Co., Omaha Brace Shop, W.A. Piel Drugs, Riggs Optical Co., and Standard X-Ray Co.[8]

Floorplan of Medical Arts Building, Floors 5 through 16. Curtis Johnson Printing Company. Image source: Douglas County Historical Society.

The Medical Arts Building was a mainstay in Omaha’s healthcare landscape for decades, and was ultimately demolished in 1999 to make way for the First National Bank tower which currently occupies the block.

[1] Schleicher, John. McGoogan Library of Medicine. “UNMC History 101: Omaha’s history of hospitals. https://www.unmc.edu/news.cfm?match=11205. Accessed May 6, 2021.

[2] Drozd, David and Jerry Deichert. “Nebraska Historical Populations.” University of Nebraska at Omaha. https://www.unomaha.edu/college-of-public-affairs-and-community-service/center-for-public-affairs-research/documents/nebraska-historical-population-report-2018.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2021.

[3] “Work on New Medical Art Building Begins.” Omaha World-Herald. Page 10. September 25, 1921.

[4] “Buildings Here Worth Twenty Million Go Up.” Omaha World-Herald. Page 12. May 23, 1920.

[5] “Medical Arts Name Will Not Change.” Omaha World-Herald. Page 14. September 20, 1925.

[6] Brochure, “Medical Arts Building.” Curtis-Johnson Printing Company, Chicago. Circa 1925.

[7] Advertisement, Omaha World-Herald. Page 12. December 13, 1927.

[8] “Directory of Tenants, Medical Arts Building.” Omaha World-Herald. Page 2. November 23, 1927.